Think Offensive - Leverage OSQuery for Discovery and Enumeration

This post has been ported from Darkwaves InfoSec blog.

TL;DR

The purpose of this post is to explain how to leverage Osquery to perform enumeration and discovery of a system without relying on Living Off the Land Binaries (LOLBins) such as net, sc, and schtasks. These tools are commonly monitored in enforced environments and used for enumerating users, services, and tasks on Windows machines.

While the post will focus on Windows machines, as they are still the mainstream in the industry, the methods described in this post can be easily translated to other platforms.

It is important to note that this post will not cover the in-depth implementation of Osquery but will instead highlight its key implementation points.

What is Osquery?

Osquery is a free and open-source tool that enables developers, security teams, and system administrators to perform high-speed, low-latency SQL queries against their operating system to gain insights and investigate issues. It allows users to treat the operating system as a relational database, where tables represent different types of system information such as running processes, loaded kernel modules, open network connections, and much more. Osquery is designed to work on multiple operating systems including macOS, Linux, Windows, and FreeBSD. It’s widely used for security monitoring, compliance auditing, and fleet management.

Brief technical breakdown of Osquery

From an offensive security researcher perspective, the following key points are important to know about the implementation of this project:

The project is built using Modern C++.

The project is designed with security in mind.

The project has numerous third-party dependencies, such as XML, JSON parsers.

The project is statically compiled.

Osquery supports various programming languages for extensions.

The daemon runs with privileged access on the system.

Sockets (Named pipes on Windows) are used as IPC between the client and server.

Finding a vulnerability in the daemon could potentially lead to privilege escalation on the system. However, as mentioned earlier in the post, the focus of this post is not to seek out flaws in Osquery but rather to leverage the intended implementation to enumerate the machine without triggering any alarms.

How Osquery Works?

Osquery is shipped with the osquery interpreter (osqueryi) and osquery daemon (osqueryd) binaries, among other components. Osqueryi functions as an interactive shell usually runs as the least privileged user, while Osqueryd acts as a daemon and runs with privileged access on the system. Both binaries utilize named pipes on Windows (sockets on other platforms) for interprocess communication (IPC).

Before delving deeper into the analysis, it is important to note that both binaries are nearly indistinguishable. They share the same source code but exhibit different behaviors based on the binary filename and parameters provided. If you examine osquery/cmake/install_directives.cmake, you will come across the following set of instructions.

[osquery_cmake_rename2osqueryi_screenshot]

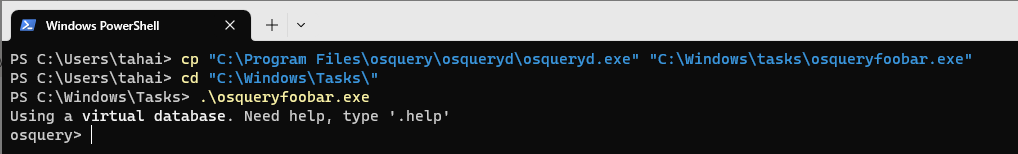

Moreover, if you examine the CMake install directives for MacOS, you will notice that osqueryi is a symbolic link to osqueryd. Furthermore, if you carefully observe the description field of both Windows binaries, you will find the phrase ‘osquery daemon and shell.’ This reinforces our previous assertion that both binaries can function as either a daemon or a shell. An effortless method to verify this is to create a copy of osqueryd.exe, rename it to a different name, and execute it.

It is important to note that osqueryi and osqueryd do not have a client-server relationship. Instead, each of them performs actions individually with different privileges. Shell interpreter implementation uses different form of local database such as sqlite, ephemeral and rocksdb.

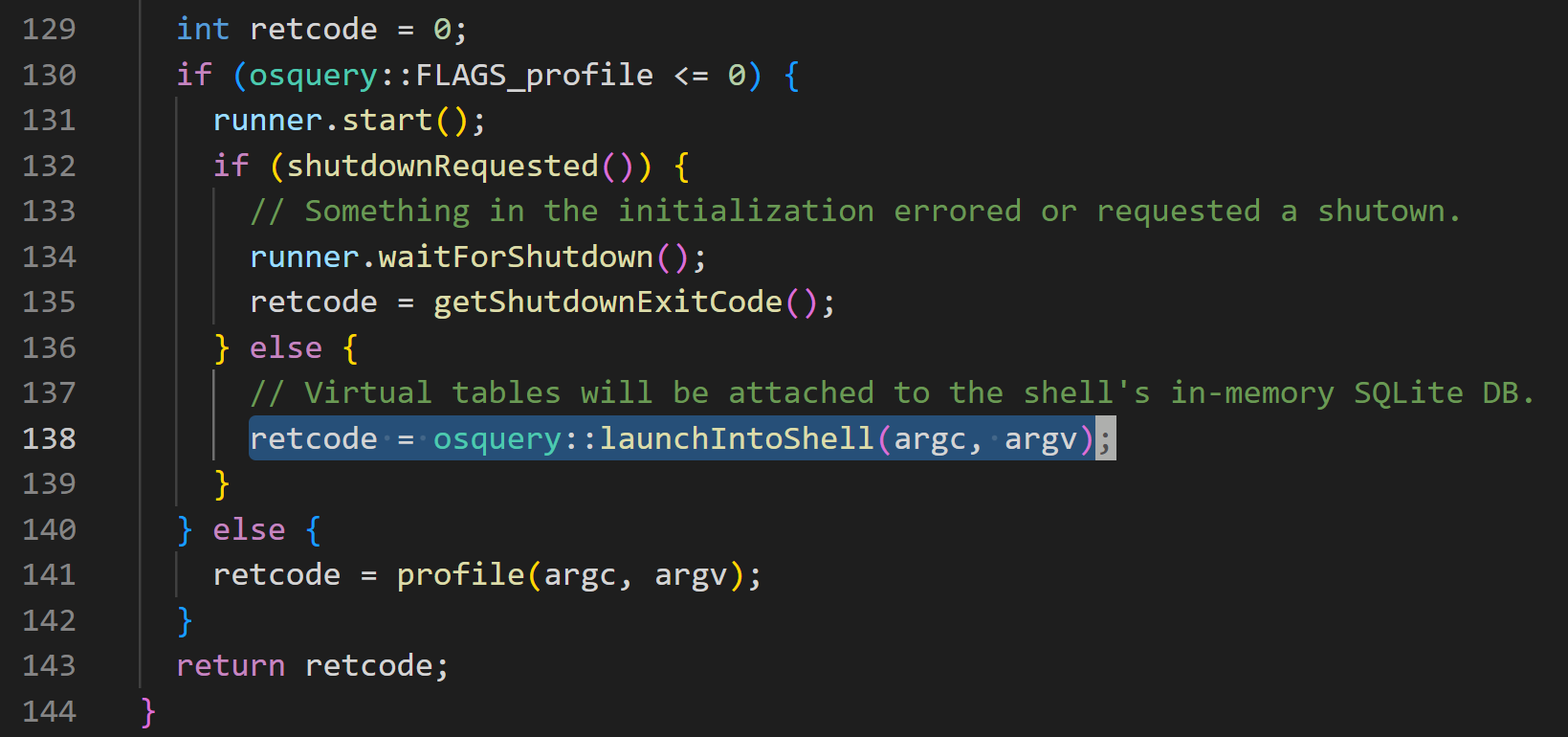

If osquery is run by a least privileged user with some missing flags, the program will run as a shell. The depth implementation of osquery is not covered in this post; however, we will cover some aspects of the IPC implementation that we can leverage later on.

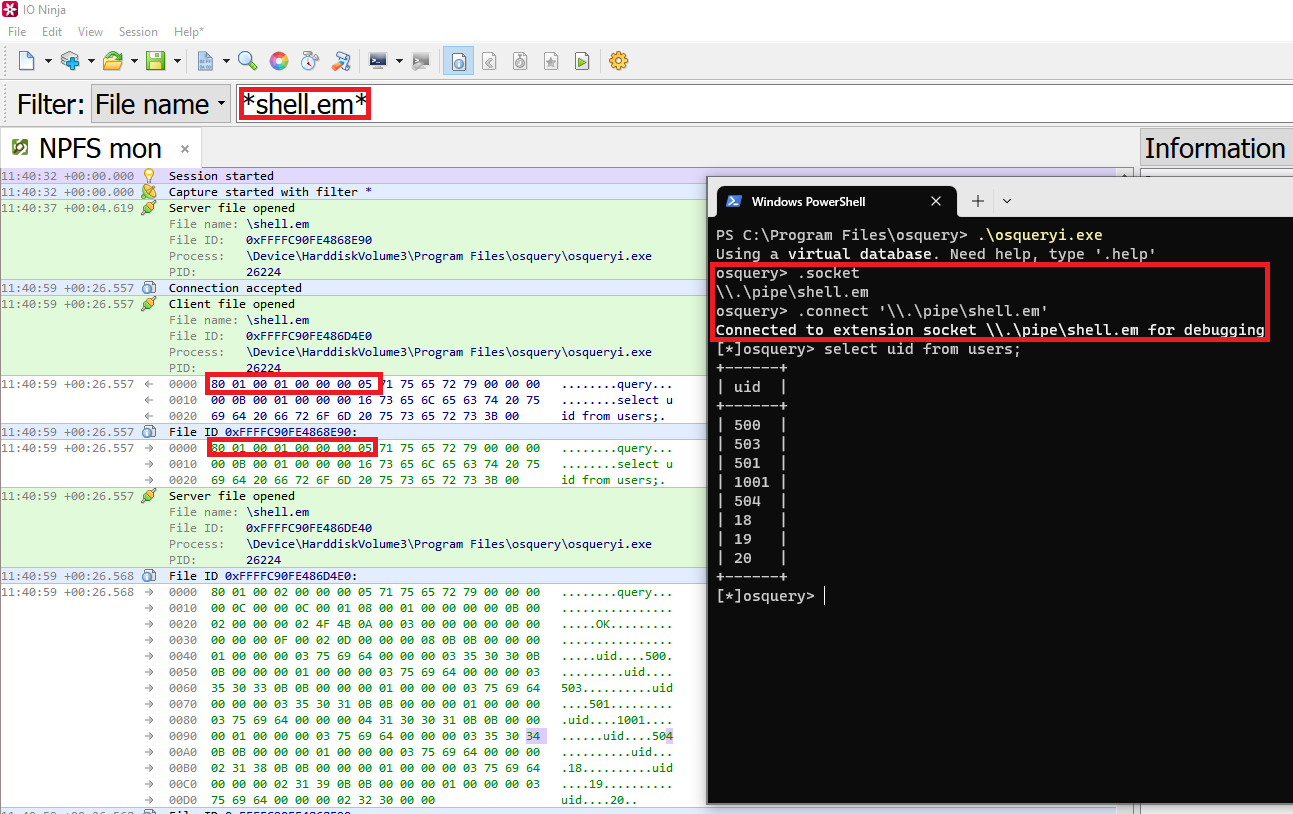

One of the key distinctions between the osquery daemon and shell in the context of IPC is that an instance of the osquery interpreter creates a named pipe with a name containing ‘shell.em’. On the other hand, if osquery is run as a service, it creates a named pipe called ‘osqueryd.em’ as shown below.

Abuse Osquery for Offensive Enumeration Purpose

Now that we have some insight into how Osquery works, we can address the main purpose of this post. Thanks to Osquery’s shell interpreter implementation, we can enumerate the system using SQL-like queries.

For instance, in the accompanying screenshot, we are listing users in the system.

Osquery has powerful built-in tables such as process_memory_map, nrfs_acl_permissions, listening_ports, pipe, ntdomains and many more, moving forward the technique depicted in the screenshot is not ideal because it requires creating a new instance of Osquery for each query. Unlike SQL, this method is unable to handle stacked queries. Although you can utilize join tables with shared columns, it adds complexity and imposes restrictions on the queries you can make.

As a workaround, we can leverage the shell’s named pipe to keep only one instance running and send as many queries as we like. From a black box perspective, we can observe that some data, along with the query, is sent to the named pipe.

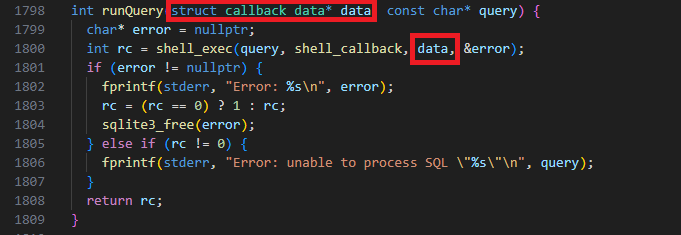

While inspecting the source, we identified that the data sent along with the query is a struct named callback_data, as shown in the following snippet.

At this point, we have several options: either reinventing the wheel or utilizing an existing implementation. For the sake of simplicity, we chose osquery-go, which provides Golang bindings for Osquery. This allows us to create a new Osquery client/extension by simply providing a socket, in this case, a named pipe.

Without further ado, the following is a video demonstrating the enumeration of the system using a tool that leverages Osquery.

%[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uLYn7zsiHDU]

The tool checks for an existing shell.em named pipe, if the named does not exists, the tool then checks for installed Osquery binary in the system and then runs Osquery in an interactive shell, which results in the creation of shell.em named pipe that then we can use to create a new Osquery client extension using osquery-go API. You can find the complete source here.

In a nutshell, this tool performs the following steps:

It checks if a named pipe called shell.em already exists.

If the named pipe doesn’t exist, it proceeds to check if the Osquery binary is installed on the system.

If Osquery is installed, the tool runs it in an interactive shell.

Running Osquery in the interactive shell creates the shell.em named pipe.

The shell.em named pipe can then be utilized to create a new Osquery client extension using the osquery-go API. You can find the complete source code for this tool here.

From a defensive perspective, monitoring named pipes with shell.em(\d)* is highly recommended. Usually, OSQuery works in conjunction with other platforms such as Kolide, among others, where data is sent to the cloud. Keeping an eye on third-party implementations is also highly recommended.

The source code of the tool can be found here.

Resources